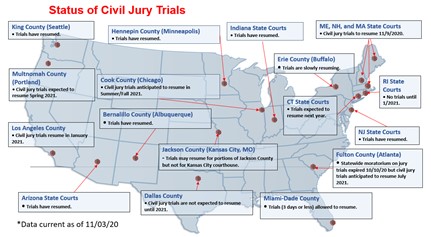

How is the Trial by Jury Being Impacted by COVID-19(NOVEMBER, 2020) - Our forefathers brought to this country a fundamental right of a trial by jury of our peers through the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution. Jury trials continue to be a staple of the American Jurisprudence. The idea that one’s guilt is decided by a jury of their peers is romanticized by Hollywood, reorganized as an inalienable right of all Americans. The Covid-19 pandemic has presented us with an inherent conflict between public safety and a constitutional right, and it appears the jury trial as we know it, may face jihad. Backlogged dockets pile up, and courts are left with no choice but to conduct jury trials through unconventional methods or even virtually. On August 11, 2020, Judge Nicholas Chu of the Travis County Misdemeanor Court in Austin, Texas presided over a Class C misdemeanor traffic violation jury trial using the video conferencing tool, Zoom. The trial was the first case in U.S. history to be tried in such a manner and presented more problems than solutions. Thereafter, many states have resumed jury trials using a hybrid method such as Arizona, Florida, New Mexico, and New Jersey. See exhibit A. These modifications to the jury trial process, from jury selection to jury deliberation could give rise to constitutional challenges based upon a denial of the right to trial by a jury of our peers.

Exhibit A (John Shaffery, Esq. – Poole Shaffery & Koegle) Jury Selection The ability to compose an impartial jury from a fair cross-section of the community is practically impossible. Vulnerable populations including low-income households and the elderly are likely to be excluded from the jury pool of virtual and traditional jury trials during the pandemic. The Pew Research Center found that nearly half of U.S. households with incomes below $30,000 a year do not have access to high-speed internet at home, and as many as 77% of senior citizens reported that they would require assistance when using a tablet or computer. While these populations are not representative of all that are excluded, a massive participation disparity is already created, and your jury panel is no longer representative of your jurisdiction. In one of the first criminal trials conducted entirely via Zoom, a Texas court addressed the disparity in technology access by giving four prospective jurors court issued technology to report for jury duty. Two of those individuals were seated as jurors, but one was excused during the oath due to connectivity problems with the court-issued device. It began with a frozen screen, and despite the court’s attempts to remedy the situation, the judge eventually excused the juror that could not access the program. A total of five jurors, over 15% of the panel, were excused due to technical difficulties ranging from computer viruses to an outdated operating system that blocked one juror’s access to Zoom altogether. How to implement voir dire to select a jury faces serious hurdles as well. Virtual voir dire poses serious problems with jurors being less than completely attentive to the process, with no way to know what could be impacting a juror’s attention. Furthermore, virtual voir dire denies attorneys the opportunity to get close enough to observe any biases jurors may express non-verbally. Conducting voir dire in-person also provides challenges as courts enforce safety procedures like screening prospective jurors for pre-existing health conditions, reconfiguring court rooms to allow social distancing, and the use of masks. While these safety procedures have shown promise in blocking the virus from penetrating institutions like the NBA bubble, they are potentially blocking an attorney’s ability to evaluate a juror’s responses which is essential to selecting a representative jury panel. Allowing potential jurors to avoid service due to health conditions that would not ordinarily preclude service will likely impair the size of the panel because anyone who shows signs of discomfort could be excused from serving. Most jury panels are made up of jurors over 52 and many over 65 years old. How do we expect these older jurors to respond to notice of jury duty when they are experiencing a fear of exposure to the virus? Furthermore, many courtrooms are not designed to accommodate social distancing, so jury selection is being moved to auditoriums, civic centers, gymnasiums and even churches. This presents a challenge when some jurors may have difficulty hearing an attorney’s questions and other jurors’ responses. In Hennepin County, Minnesota (Minneapolis), the state determined that only (5) courtrooms had appropriate spacing for the trials, including all lawyers, witnesses, and court personnel. With respect to the cases tried in Hennepin County, the state is flipping the courtroom so that the gallery is being used for jury selection which allows the jurors to be spaced out at appropriate distances. The Federal court jury trial system is less impacted than state courts. Federal jury trials typically require six jurors with possible alternates while many states require 12 jurors and sometimes as many as three alternates. Therefore, the number of jurors summoned for a federal trial is significantly smaller than the veniremen summoned in state courts. An additional advantage is that many of the federal courts are newer and much more spacious while many of our state courts are old with small courtrooms and limited jury boxes and seating. In fact, it has been reported that in Massachusetts’s state courts, judges are telling counsel, “you are getting a jury of six and not 12 and is not even asking counsel to stipulate to the smaller jury.” With respect to the use of masks, concealing facial expressions is problematic. Often during voir dire, a facial expression of a prospective juror in response to a question asked of another juror will cause an attorney to ask that juror to respond to the previously asked question as well. This issue even came up at the confirmation hearing of recent Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett. Many were concerned about not being able to see her facial expressions during her confirmation hearing. The Trial Michigan trial courts conducted more than 1.3 million hours of court proceedings via Zoom by the end of September 2020. The quick transition to digital dependence caused by the pandemic has its pitfalls but it has also provided us with moments of humor. During the onset of Supreme Court oral arguments in May, as Chief Justice Roberts reprimanded the court for ringing cellphones and then he was interrupted by the sound of a toilet flushing. Although the official transcript does not make note of the flush, I think we can all agree, res ipsa loquitur, “the thing speaks for itself.” However, toilet flushing is the least of our sticky situations as we attempt to digitize the legal system. COVID-19 driven modifications present an overwhelming amount of challenges to the actual trial. Anyone who has experienced video conversations through FaceTime knows that there is no replacement for human interaction. Non-verbal communication is lost almost entirely on videoconferencing platforms like Zoom. The Social Psychology of Telecommunications provides that useful information like subtle eye movements and other non-verbal communication cues are not likely to be picked up on video. And where a typical Zoom call frames the individual from the chest up, jurors cannot see any body language communicated by the lower half of the body. This severely distorts a juror’s ability to properly observe witnesses, their testimony, and evidence. As the sole judges of witness credibility, it is imperative that jurors be able to view witnesses and other jurors body language and non-verbal cues in their assessment. Factors such as video quality, lighting, and angles could trigger biases in jurors as well. Witnesses speaking on behalf of wealthy defendants could appear more attractive and sincere as they sit in front of extravagant backgrounds and have superior video quality. We cannot even guarantee that witness testimony is candid in a virtual setting. What occurs off camera cannot be seen which could impact a witness’s testimony. Additionally, jurors cannot possibly remain impartial when their ability, or lack thereof, to properly evaluate evidence is compromised by the limitations of videoconferencing. Erie County, New York (Buffalo), has resumed in-person trials & voir dire. They have two designated courtrooms – one for evidence presentation and one for a juror breakroom. In these courthouses, no other court business shall be conducted during trial. Attorneys may not approach witnesses – all evidence is handed to the court officer, then court officer displays evidence to the jury. Evidence does not always come in the form of a document, or in a form that can be shared via a file share program. Thus, where digital distribution or in-person display does not equate to physical interaction, the impact of evidence on jurors is certainly diminished. Jury impartiality continues to be at issue even as some courts move on to conducting in-person trials. In Hennepin County, Minnesota (Minneapolis), once the jury is selected, the jurors are then spread across the gallery. Only one attorney is allowed at each table along with client. Before a witness testifies, they take down their mask to show the jury their face but then wear the mask the remaining time. From that point forward the trial is conducted in traditional fashion. The use of face masks and social distancing protocol present similar challenges. Jurors are still unable to observe witness facial expressions and subtle nuances in their demeanor to make a proper assessment of credibility. Jury Deliberations Jury secrecy is essential to the work of juries to protect the integrity of deliberations and reassure open discussions. Thus, any modification to this sacred process poses a serious question of whether the trial by jury has been impaired to a level it has violated this constitutional right. As courts are forced to modify several functions of the jury trial in light of a global health emergency, this includes jury deliberations. When conducted virtually, how do we ensure all jurors are able to participate in the deliberations without monitoring their deliberations? If one of the other jurors cannot hear or see their fellow jurors, is it another juror who fixes the computer glitch or do they call someone else? Who exactly do they call? These questions must be approached very carefully to guarantee that jury deliberations do indeed remain secret. A recent study conducted by Dubin Research Consulting presents that 74% of potential jurors experience feelings of anxiety about being in close physical proximity with others. Courts that have resumed in-person trials attempt to relieve this concern by conducting jury deliberations in the larger courtroom instead of the smaller rooms actually designated for deliberations. In King County (Seattle), the court has been holding trials in a conference center rented in a nearby town. Deliberations take place in large conference rooms separate from the rooms in which the trials are held. Nevertheless, jurors are still likely to feel some level of anxiety, interrupting their decision-making ability, during a very crucial moment of the jury trial process. We are undeniably fortunate that advancements in technology have enabled our justice system to persist amidst a global pandemic. But we cannot ignore the consequences and limitations. In the face of the pandemic, courts in Johnson County, Kansas organized the Ad Hoc Jury Trial Task Force and court issued a 30-page order with the task forces suggestions for conducting jury trials under pandemic conditions. Many states have followed suit and although these challenges are daunting, special bench bar committees and experts continue to evaluate and develop alternatives methods in an effort to safeguard a sacred right unique to our country -- a right to trial by jury. However, even in taking all the necessary precautions, some courts have found it impossible to preserve the rights of litigants while also ensuring safety. In the U.S. District Court of Nebraska’s November 2nd order regarding the postponement of jury trials, the court stated: The resurgence of the COVID-19 pandemic in the District of Nebraska, and the increased community transmission of that disease, have again reached the point at which the Court's proceedings are affected. . .. In that environment, despite the physical distancing measures in place, the Court is presently unable to draw a venire, select a jury, and try a case to completion in a manner consistent with the right to a fair cross-section of the community or due process for the litigants. And it is the Court's responsibility, as a careful steward of public safety, not to unnecessarily or unduly endanger its own personnel, other participants in the judicial process, or members of the community. (See General Order 2020-14). Since the founding of the United States, our courts have considered the intersection of the legal system and public health. The founders had ample experience with smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, typhoid, and malaria. Covid-19 is just another obstacle in the long line of illnesses which have threatened American Jurisprudence. At this moment in time, it is unclear what the next step will be in preserving the sanctity of the American Jury trial. But one thing is guaranteed, the American Jurisprudence system will persevere and prevail, so that the next time we are faced with such an enemy, we will be ready. Author Bios Daniel F. Church For more than 30 years, Daniel F. Church has been representing local, regional, and national companies in civil litigation, both in federal and state courts. He represents defendants in class action suits, as well as in cases involving toxic torts, bad faith, railroad, premises liability, professional liability, product liability and general tort claims. He has tried more than 40 cases before juries, many involving damage claims in excess of one million dollars and has represented clients in civil trials in 15 states. Mr. Church was selected as one of the "Best Lawyers in America" by his peers and as a Super Lawyer in the Kansas City area. Mr. Church is currently on the Board of Directors for the Professional Liability Defense Federation. Shawn A. Meyer Shawn A. Meyer went to Chicago Kent College of Law and earned his Juris Doctorate Degree with a certificate in Business Law. Shawn currently resides in Kansas City, Missouri where he works as a Civil Litigation attorney at Morrow Willnauer Church, LLC. - (Morrow Willnauer Church, L.L.C.) |